The evaluation and management of the case of an 11-year-old patient with gallstone pancreatitis presenting to the emergency department

Highlight box

Key findings

• Our case represents a case of paediatric gallstone pancreatitis which was treated with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatogram with stent insertion. Following this acute episode, our patient was treated with laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

What is known and what is new?

• Acute pancreatitis in the paediatric population although relatively rare, needs to be considered in the differential diagnoses of upper abdominal pain. We have highlighted in our case that a high index of clinical suspicion is required to ensure for a timely diagnosis.

• Identifying risk factors including family history of gallstones and obesity are important factors in the paediatric history that need to be actively evaluated.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• One of the main challenges as faced in this case was assessment of the volume of fluid requirement in the resuscitation and maintenance phases of patient treatment. This can be considered either in terms of ideal body weight or actual body weight in the child especially in the child with a high body mass index.

Introduction

Acute pancreatitis is a relatively rare paediatric presentation of acute abdominal pain with an incidence of 1 in 10,000 children. Whilst most cases of acute pancreatitis in the adult population is due to alcohol excess and gallstones (up to 60%), in the paediatric population the underlying aetiology (1,2) can range from medications, infection, trauma as well as underlying structural abnormality.

Increased production or reduced clearance of bile (bile stasis) are the causative factors for formation of gallstones. A high index of clinical suspicion is required to establish the underlying diagnosis with timely management of the condition. This is particularly important in the context of non-specialist paediatric centres as highlighted in our case. The clinical course of acute pancreatitis can range from mild pancreatitis to severe pancreatitis leading to major complications. In a study done by Bhanot et al. in 2022 (3), the complication rate arising from acute pancreatitis was noted to be as high as 20% in the study population. The most common complications noted were development of pancreatic necrosis and respiratory failure. However, the most concerning result from the study was that at 1 year post diagnosis only 59% of paediatric patients had a full recovery. This highlights the fact that acute pancreatitis in the paediatric population although presenting as mild pancreatitis can have long-term impact on the child’s health. We present this article in accordance with the CARE reporting checklist (available at https://pm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/pm-24-5/rc).

Case presentation

We present the case of an 11-year-old girl with acute abdominal pain with multiple episodes of vomiting in the paediatric Emergency Department. This presentation was preceded by several distinct bouts of severe self-resolving abdominal pain that was described by the patient as colicky in nature. There was no reported change in bowel habit. There were no associated symptoms of general malaise in between these episodes. She had presented to the emergency department a week previously and was treated as reflux and following a fluid challenge was discharged home. There was no gynaecological history with her menarche having started recently. In the Emergency Department, her venous blood gas revealed hypokalaemia metabolic alkalosis (pH 7.45) with a markedly raised lactate of 6.5. She had no past medical or surgical history to note. She was neither on any regular medications nor had any allergies. The only significant family history was that three members of the family had gallstones—mother, older sibling and maternal grandmother.

Observations

The initial observations are shown in Table 1.

Table 1

| Characteristics | Results |

|---|---|

| Temperature (tympanic), ℃/℉ | 35.6/96.1 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 115 |

| Blood pressure, mmHg | 109/65 |

| Respiratory rate, breaths/min | 27 |

| Oxygen saturations, % | 97 |

| Conscious level | 15 |

On examination of the abdomen there was noted discomfort in the right upper abdomen and in the epigastric regions, however, there was no evidence of peritonitism. She was noted to be clinically dry and pale in colour. There were no other pertinent examination findings. Her body mass index (BMI) at presentation was 29.3 kg/m2.

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s parents for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Investigations

On her initial blood tests, she was noted to have a markedly raised serum lipase level, however with time and treatment this improved (Table 2). She was noted to have both raised serum gamma glutamyl transferase (GGT) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) levels. In addition, the admission blood highlighted a marked neutrophilia (Table 3). She was treated with intravenous antibiotics. The initial antibiotics administered were intravenous co-amoxiclav 1.2 gms TDS and metronidazole 500 mg TDS for 3 days. However, following discussion with microbiology this was escalated to piperacillin/tazobactam 4.5 gms TDS and metronidazole 500 mg TDS for a further 21 days. She had multiple blood cultures sent at intervals, however no specific organisms were isolated.

Table 2

| Liver function tests | Admission | Day 2 | Day 4 | Day 7 | Day 14 | Day 28 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALT (mmol/L) | 255 | 61 | 29 | 16 | 31 | 31 |

| ALP (mmol/L) (ref: 30–130) | 205 | 92 | 87 | 103 | 121 | 106 |

| Bilirubin (μmol/L) | 23 | 15 | 13 | 7 | 7 | <3 |

| Albumin (g/L) (ref: 35–50) | 47 | 23 | 22 | 26 | 30 | 29 |

| GGT (IU/L) (ref: 0–30) | 169 | 37 | 34 | 32 | 30 | 28 |

| Lipase (U/L) | 14,415 | 1,297 | 180 | 126 | 73 | 60 |

ALT, alanine transaminase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; GGT, gamma glutamyl-transferase.

Table 3

| Full blood count | Admission | Day 2 | Day 4 | Day 7 | Day 14 | Day 28 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC (×109/L) (ref: 3.6–11) | 28.8 | 26.4 | 16.4 | 11 | 8.6 | 4.7 |

| Hb (g/L) (ref: 115–165) | 164 | 156 | 128 | 127 | 117 | 113 |

| HCT (L/L) (ref: 0.37–0.47) | 0.46 | 0.59 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.34 | 0.33 |

| Neutrophils (×109/L) (ref: 1.8–7.5) | 21.96 | 23 | 14 | 8 | 6 | 1.5 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) (ref: <5) | <1 | 53 | 270 | 16 | 3 | 3 |

WBC, white blood count; Hb, haemoglobin; HCT, haematocrit.

In terms of imaging, she underwent ultrasound scan (USS) of the abdomen and pelvis (Figure 1 on admission) (22/12/2023) which revealed multiple gallstones within a thin-walled gallbladder with a significantly dilated common bile duct (CBD). In order to assess of interval, change in the previous findings she underwent a repeat US of the abdomen (Figure 2) (25/12/2023) which demonstrated an interval increase in free fluid on the right side of the abdomen with evidence of bilateral pleural effusion.

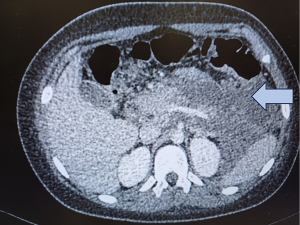

Follow up imaging was carried out with computed tomography (CT) abdomen and pelvis (Figure 3) (01/01/2024) to assess the pancreas as well as review of the abdominal free fluid. This revealed severe interstitial oedematous pancreatitis with a large ill-defined fluid measuring 13 cm × 10 cm × 22 cm craniocaudal surrounding the pancreas, spleen, stomach, in the lesser sac, left paracolic gutter and perirenal space. In order to delineate the biliary structures, she underwent magnetic resonance cholangiopancreaticogram (MRCP) (Figure 4) (10/01/2024) which demonstrated similar findings to the previous CT. The MRCP did confirm the presence of gallstones within the gallbladder and in the distal CBD.

Sequence of events

Having been diagnosed with acute gallstone pancreatitis, our patient was initially admitted locally under the paediatric team with general surgery input. The following day she was transferred to the tertiary children’s hospital for joint care between paediatric general medicine, hepato-biliary and paediatric gastroenterology. Unfortunately, she was noted to have multi-organ dysfunction, she had close monitoring with the various specialist teams with close monitoring by the paediatric intensive care teams.

Initially, she was administered fluids based on her ideal body weight (IBW), however, this was noted to be inadequate in terms of urine output. In view of this her daily fluid administration rate was subsequently increased to cater for this. However, she was noted to have symptoms and signs of fluid overload which required supplemental oxygen therapy and diuresis with intravenous furosemide. administration of intravenous furosemide was required which improved her respiratory status. To meet her nutritional needs, she had total parenteral nutrition with regular input from the nutritional team. Analgesia was optimised and delivered in the form of patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) as there was increasing analgesic requirement. She underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatogram (ERCP) with sphincterotomy as an inpatient due to the presence of CBD stone. She had a stent inserted at the time of the procedure (Figure 5) (14/1/2024). Following a period of close observation, repeat CT imaging was carried out to assess the size of the collection (Figure 6). At repeat CT imaging of the abdomen, the size of the peripancreatic collection was noted to have improved (Figure 6) (17/1/2024). Whilst being an inpatient she underwent genetic testing to ascertain if there was a genetic predisposition to the formation of gallstones.

Symptoms at discharge

Following the prolonged inpatient management of 28 days, she was discharged having recovered from the acute illness. At discharge, the pain was noted to be controlled with simple analgesia (paracetamol and codeine when needed).

Follow up

Following her initial acute presentation with gallstone pancreatitis, she underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy at one month and was subsequently reviewed in the outpatient clinic. She was noted to be doing well with regular follow up by the paediatric gastroenterology team.

Discussion

The differential diagnoses of abdominal pain in our patient were:

- Acute cholecystitis—this was excluded by the presence of a thin-walled gallbladder with the absence of pericholecystic fluid.

- Acute pancreatitis—this was confirmed to be the diagnosis with markedly raised lipase, GGT and evidence of CBD dilatation.

- Although low in the list of differentials, early diagnosis of diabetes was also considered—however blood gas highlighted alkalosis and blood ketones were noted to be 0.7. other investigations to exclude a diagnosis were also carried out.

The aetiology of biliary pancreatitis in the paediatric patient can range from CBD to biliary tree abnormalities. There can be several predisposing factors that are like adult patients that include chronic haemolytic disease, ileal disease and chronic liver disease (4,5).

The diagnostic criteria for acute pancreatitis in children require one of the three characteristic features:

- Serum amylase or lipase ≥3 times the upper limit of the normal range.

- Radiographic evidence of acute pancreatitis (changes in the pancreatic parenchyma or the presence of peripancreatic fluid).

- Serum lipase >1.5 times the upper limit with 2 out of the 4 clinical features—abdominal pain typical of acute pancreatitis, nausea or vomiting or the presence of epigastric pain.

Historically acute pancreatitis due to gallstones was previously noted to be a rare entity in the paediatric population (6-8). More recently with increasingly worrying levels of childhood obesity and with the more widespread use of ultrasound the incidence of gallstones as a cause of pancreatitis has increased (9).

Like adults, USS of the abdomen is the initial choice of investigation in the diagnosis of gallstone pancreatitis, however the accuracy is noted to be 75–80% and is operator dependent. Ultrasonographic views may be limited by overlying gas, thereby needed more dedicated imaging with CT or MRC in some cases (10,11).

Whilst there are several scoring systems that categorise the severity of acute pancreatitis in adults, for paediatrics the scoring systems are less validated and documented in the literature. The paediatric JPN score incorporates parameters from both the Glasgow and Ransom scoring system (12,13). There is currently increasing use of CT to evaluate the severity of acute pancreatitis (12).

Pancreatitis and fluid administration—the challenge

One of the challenges in the management of acute paediatric pancreatitis is the volume of fluids administered which needs to be more cautious in comparison to the adult patient. The presence of pulmonary oedema and pleural effusion is likely to be multifactorial.

The two main factors to consider are:

- the severity of the gallstone pancreatitis could contribute to the development of mild acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). This only required supplemental oxygen therapy without the need for more advanced oxygen delivery or ventilation strategies.

- Initially the volume of fluid was determined by the patient’s IBW (14), however the volume was noted to be inadequate thereby the rate of fluid administration was increased which might have led to the development of fluid overload.

There is limited literature highlighting the optimal volume of fluids that can be administered in paediatric patients. However, a consensus from the NASPGHAN Pancreas Committee (15) recommends that intravenous fluid administered is 1.5–2 times the maintenance daily volume with close urine output over the following 24–48 hours. However, even with this relatively restrictive fluid strategy the paediatric population is prone to the development of acute lung injury. This warrants a strict input/output monitoring with low index of suspicion for the development of complications by the treating clinicians. Based on the NASPGHAN recommendation when more aggressive fluid resuscitation is being undertaken, 4-hourly observations of the oxygen saturation, blood pressure and respiratory rate are needed over the first 48 hours. In adults, the target urine output is 0.5–1 mL/kg/h, until paediatric specific guidelines are available, this was recommended to be suitable target for urine output.

Knowledge gap

As aforementioned, there are limited data on what constitutes ideal volume of resuscitation fluid and whether this should be based on IBW or actual body weight in the overweight paediatric patient with acute pancreatitis.

Strengths and limitations

One of the main strengths of our case report was the ability for us to share the detailed results from the images. The other strength of this case report was that—as the authors of the case and attending clinicians (emergency medicine), we were involved in the patient management from the start of our patient’s journey.

One of the main limitations of this case report was that we were able to provide details from the immediate and medium-term management. It would be interesting to understand the disease process and its associated long-term sequelae (if any). For future research, we plan to review case series of similar presentation and gain a further understanding of the measures undertaken to limit/avoid the complications leading to fluid overload.

Conclusions

The diagnosis and management of paediatric pancreatitis can be challenging and requires a multidisciplinary approach. Concerns about administration of large volumes of crystalloids continue to be a concern, thereby strict fluid balance monitoring is required. Although the exposure to ionising radiation needs to be limited in the paediatric patient, it is vital to assess for complication including complex intra-abdominal collection as highlighted in this case. There is a need for further research in the domain of fluid resuscitation in paediatric pancreatitis as highlighted in this case. We have also highlighted that until specific guidelines are established with regards to the aforementioned, aiming for urine output of 0.5–1 mL/kg/h is a reasonable target.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank all the teams involved in the care of our patient for their concerted efforts to ensure our patient recovered in a timely manner, and thank patient’s parent for giving us this opportunity to share this unique learning opportunity including sharing the patient’s investigations.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the CARE reporting checklist. Available at https://pm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/pm-24-5/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://pm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/pm-24-5/prf

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://pm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/pm-24-5/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s parents for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Banks PA. Epidemiology, natural history, and predictors of disease outcome in acute and chronic pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc 2002;56:S226-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yadav D, Lowenfels AB. Trends in the epidemiology of the first attack of acute pancreatitis: a systematic review. Pancreas 2006;33:323-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bhanot A, Majbar AA, Candler T, et al. Acute pancreatitis in children - morbidity and outcomes at 1 year. BMJ Paediatr Open 2022;6:e001487. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Park A, Latif SU, Shah AU, et al. Changing referral trends of acute pancreatitis in children: A 12-year single-center analysis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2009;49:316-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Choi BH, Lim YJ, Yoon CH, et al. Acute pancreatitis associated with biliary disease in children. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2003;18:915-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Haddock G, Coupar G, Youngson GG, et al. Acute pancreatitis in children: a 15-year review. J Pediatr Surg 1994;29:719-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hudson JM, Beasley SW. Abdominal pain: is it appendicitis? In: Hudson JM, Beasley SW, editors. The Surgical Examination of Children. London: Heinemann Medical Books; 1988:16-24.

- Greenfeld JI, Harmon CM. Acute pancreatitis. Curr Opin Pediatr 1997;9:260-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ma MH, Bai HX, Park AJ, et al. Risk factors associated with biliary pancreatitis in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2012;54:651-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sutton R, Cheslyn-Curtis S. Acute gallstone pancreatitis in childhood. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2001;83:406-8. [PubMed]

- Lugo-Vicente HL. Trends in management of gallbladder disorders in children. Pediatr Surg Int 1997;12:348-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Holdstock V, Macqueen Z, Amjad SB. 1628 Determining standard practice for IV fluid monitoring and prescribing in overweight children. Arch Dis Child 2021;106:A434.

- Suzuki M, Sai JK, Shimizu T. Acute pancreatitis in children and adolescents. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol 2014;5:416-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shimizu T. Pancreatic disease in Children. J Jpn Pediatr Soc 2009;113:1-11.

- Abu-El-Haija M, Kumar S, Quiros JA, et al. Management of Acute Pancreatitis in the Pediatric Population: A Clinical Report From the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Pancreas Committee. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2018;66:159-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Chowdhury D, Rameto A. The evaluation and management of the case of an 11-year-old patient with gallstone pancreatitis presenting to the emergency department. Pediatr Med 2024;7:26.