危重儿童的能量消耗

在危重儿童中,充足的能量摄入有助于改善临床预后[1-3],因此入住儿科重症监护病房(pediatric intensive care unit,PICU)期间,能量需求的确定具有挑战性,须避免喂养不足和过度喂养的发生。由于缺乏测量设备,危重患者的能量需求很难评估。能量需求取决于不同疾病阶段(即急性期、稳定期和恢复期)的需求,同时也受疾病严重程度和其他因素,如镇静、肌肉松弛剂、机械通气和发热等的影响。为确定危重儿童的能量需求,静息能量消耗(resting energy expenditure,REE)可用间接量热法(indirect calorimetry,IC)测定或预测公式计算,在某些情况下,还需考虑疾病和活动因素。

1 IC法测定危重患儿的REE

1.2 健康儿童的总能量消耗组成

健康儿童的24 h TEE由基础代谢率(basal metabolic rate,BMR)、食物的热效应、活动消耗、生长所需组成,极少数情况下还包括寒冷产热[4]。BMR是总能量消耗(total energy expenditure,TEE)的主要组成部分,可以认为是身体各器官和组织能量消耗的总和[4-5],用kcal/(kg·d)表示。由于婴儿和幼儿机体高代谢器官的占比相对较大,其BMR相对较高。生长所需的能量用于蛋白质和脂质的合成,以及新形成的组织中的能量沉积[4],这类能量消耗对于快速生长的婴儿(约至12月龄)和青春期儿童[6]尤为重要,因此,与较大儿童和成人相比,婴幼儿的TEE较更高(图1)。

精确测定BMR需要非常严格的条件,包括禁食至少12~14 h、清醒状态、舒适仰卧位、测量前1 d无剧烈运动等[4],现实中很难满足以上条件,因此大多数研究仅测定REE,即机体静止、无肌肉运动状态下的能量消耗。通常情况下,REE略高于BMR(可达10%),常被用作BMR的替代指标。

1.2 IC测定REE的主要原理

临床实践中测定REE仍以IC为主,IC的原理是体内底物氧化产能与耗氧量(VO2)和二氧化碳产生量(VCO2)相关[8]。在细胞水平上,代谢相关的VCO2和VO2的比率称为呼吸商(respiration quotient,RQ):RQ=VCO2/VO2[8],RQ和释放的能量取决于被氧化的特定底物,见表1。如100克葡萄糖氧化的化学计量方程式如下[8]:

C6H12O6+6O2=6CO2+6H2O+673 kcal (RQ=1) [1]

多种公式已被用于从由VO2和VCO2计算REE,其中以Weir公式最为常用[9]:

REE (kcal/d)=5.50VO2 (mL/min)+1.76VCO2 (mL/min)–1.99总尿素氮(g/d) [2]

IC测定REE通常在严格条件短时间(30 min~2 h)进行,该测定值主要用于24 h REE计算。

1.3 IC测量在PICU中的实际应用

为确定危重儿童的能量消耗并指导营养支持,欧洲儿科和新生儿重症监护学会(ESPNIC)、美国肠外肠内营养学会(ASPEN)建议在危重疾病的急性期后使用经过验证的间接热量计测量REE[10-11]。对于可行IC测量的目标患者提出了11条标准(表2)[12]。根据这些标准,超过70%的PICU的儿童需进行IC测量[13]。

使用IC测定REE需要经济、技术和人力资源等多方面支持,这也是为什么全球仅有少数PICU(全球10%~17%的PICU)使用间接热量计[1,14-16]。在机械通气患者中,有些情况,诸如吸入氧浓度过高、气管导管周围泄漏或湿度改变等,可能会导致测量不准,因此临床医生须确保设备精确校准和床旁有效测量。直至最近,大多数PICU仍使用Deltatrac II(Datex-Ohmeda,Helsinki,Finland),该产品在危重成人和儿童中经过验证[17-19],但该设备现已停产。目前,在成人使用的间接热量计(M-COVX,Datex-Ohmeda,Finland;Quark RMR and Q-NRG+,Cosmed,Italy,CCM Express,Medical Graphics Corp,UK)中,没有一个在机械通气的危重儿童中得到验证。因此,经验证的可用于儿科群体[包括新生儿、婴儿以及吸入氧浓度高(高达60%~70%)的患儿等]的热量计亟待开发。

2 通过预测公式估计危重儿童的REE

2.1 健康儿童可用的预测公式

作为使用IC测定REE的替代法,预测公式可用于REE估算。有多种REE的预测公式,其中大部分都基于年龄、性别、体重和身高进行计算。国际营养指南[10-11,20]建议将危重患儿的准确体重代入Schofield公式以估算REE[21],表3列举了不同性别和年龄段儿童的Schofield公式。

2.2 常用REE预测公式在危重儿童中的有效性

据一项全球调查[15]报道:多数PICU通过采用预测公式评估REE,包括Schofield公式(25%)[21]、World Health Organization公式(25%)[5],甚至Harris-Benedict公式(17%)[22]。

Schofield公式[21]的有效性已在许多针对危重儿童的研究中得到评估。研究结果[23]表明:2个Schofield公式(连同Talbot表[24])相比于其他方程是最准确的。尽管如此,与IC测量的REE(mREE)相比,Schofield公式预测的REE在mREE±10%范围以内的仅占35%,这些预测方程可能低估了幼儿的REE,而高估了大龄儿童的REE[25]。

营养指南[10-11]亦不建议在危重儿童中使用Harris-Benedict公式[22],该公式是为计算健康成人REE设计的。强有力的临床证据表明Harris-Benedict公式高估了大多数儿童REE,从而导致过度喂养的风险。

2.3 为预测机械通气儿童REE而设计的特定公式的有效性

有一些REE预测公式是专为某种特定疾病或状况的人群设计的,包括机械通气危重儿童,即White等[26]、Meyer等[27]和Mehta等[28]分别在2000年、2012年和2015年提出的公式。一些研究[23,25,29]对White等[26]和Meyer等[27]的公式进行了有效性评估,结果表明这些公式并不准确,而Mehta等[28]于2015年设计的预测公式有望接近真实值。该公式不是传统公式,它需要测量VCO2,并在Weir公式[9]中将RQ取固定值0.89。一项针对体外循环后儿童的最新研究[30]发现公式偏倚的最重要决定因素是RQ;另一组研究结果表明:在该公式中代入由Servo-I®和Capnostat-III传感器测量的VCO2,其REE预测值在体重超过15 kg的儿童中是准确的,而对于较小体重的儿童则不准确。主要问题在于,对于体重小于15 kg的儿童,传感器无法准确测量VCO2。因此,还需进一步评估Mehta等公式的有效性,同时用于测定体重低于15 kg儿童VCO2的传感器也有待开发。

3 重症监护条件对危重儿童REE的影响

3.1 危重儿童的能量消耗

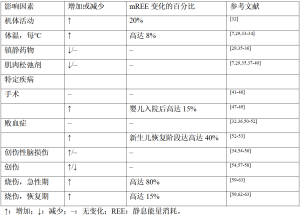

危重儿童处于安静卧床状态,所在环境温度为中性温度,没有肢体活动,镇静并进行规律的机械通气治疗,因此,其能量消耗低于健康儿童(图1),故通常认为疾病急性期的TEE与REE相等。几项主要针对接受机械通气治疗儿童的研究调查了重症监护治疗期间机体能量消耗的影响因素(表4)。

Full table

3.2 机械通气儿童REE值的日常变化

因各种内外科疾病接受机械通气的儿童,入PICU第1周内,未观测到mREE的显著日常变化[7,37-38,50-51,64]。这意味着在机械通气期间,儿童机体内部的mREE没有显著变化。

3.3 体温

体温是影响个体mREE的最重要因素[26]。一项对74名接受机械通气危重儿童的研究[7]发现:体温每升高1 ℃,mREE就会增加8%。其他多项研究[29,33-34]也证实了这种正相关性:体温每变化1 ℃,MREES变化在6%~8%。

3.4 药物

镇静药物和血管活性药物常用于危重儿童的治疗,这些药物也会影响mREE[29,37]。一项纳入了57名年龄介于9个月至15.8岁、接受机械通气治疗儿童的研究[29]表明:当使用镇静药物时,mREE在82%的儿童中低于通过预测公式估计的REE,但该结果并未在其他研究中得到证实[35-36]。某些针对机械通气儿童的研究[7,29,39]表明:肌肉松弛剂也会降低mREE,下降比例多在6%~10%,也有个别研究报道降幅可达36%[35],而其他一些研究则报道肌肉松弛剂的使用不影响mREE[37-38,40]。

3.5 食源性产热

据推测,营养支持的数量和方式会影响危重患者的能量消耗,但迄今为止没有研究证实这一影响[29,35],其原因可能在于大部分研究中使用了持续的营养支持。

3.6 机体活动

一项针对7名危重儿童的研究[32]在儿童入住PICU的6 d内,应用双标水法对儿童的TEE进行了测量,测得的TEE比REE高20%,这一增加的能量消耗与加速度计记录的机体活动有关[32]。因此在计算危重儿童的总能量需求时,对入住PICU至少1周的儿童还应考虑机体活动水平。

3.7 特定疾病

3.7.1 手术

研究[47-49]发现:术后入住PICU婴儿的mREE会在术后可迅速增加,术后4 h达峰值,增幅最高可达15%。但婴儿mREE在术后的增加是暂时的[47-49],其很快便能恢复到术前水平[41-43]。而在年龄较大儿童的研究中,术后mREE并未增加[44-46]。

3.7.2 败血症

一项针对10名自主呼吸的败血症新生儿的研究[53]发现:与健康对照组相比,mREE(每天均值57±3 kcal/kg)在脓毒症发生后的第1~3天增加20%,第4天增加15%。另一项针对19名脓毒症新生儿的研究[52]发现:mREE从急性期每天49±13 kcal/kg一直增加至恢复期每天68±11 kcal/kg。对此作者认为mREE的增加可能是生长恢复所致。而在患有败血症的大龄儿童中,mREE与其他诊断危重儿童及健康对照组相比没有差异[32,36,50-51]。

3.7.3 创伤性脑损伤

尽管20世纪80年代的2项研究[54-55]发现严重创伤性脑损伤儿童的mREE可增至REE预测值的2倍,但上述高代谢状态并未在近期的研究中得到证实[34,56]。这可能是由于治疗的差异,因为多年来有关这些患者的镇静、麻痹和温度控制的指南已经发展。因此在创伤性脑损伤的儿童中,REE可能取决于疾病阶段和患者的神经系统状态。

3.7.4 创伤

仅有少数研究[54,57-58]测量了在不同人群中严重创伤儿童的REE变化情况,结果发现mREE降低和增加的情况均有出现。

3.7.5 烧伤

近期一项对危重成人和儿童的系统综述得出的结论[65]表明:体表面积烧伤百分比和烧伤后天数均与mREE相关。一些研究[59-63]发现:与预测的急性期REE相比,烧伤儿童的mREE的增加高达180%。此外,尽管REE在恢复期逐渐下降,烧伤后的mREE在数月甚至数年内仍比预测的REE高(部分高达15%)[59,62-63]。这种高代谢状态被认为是由烧伤患者增加的促炎细胞因子[61,66-67]、儿茶酚胺和应激激素[61-62]介导的。这些研究表明,影响危重儿童REE的主要因素是体温和身体活动。此外,烧伤也可能对能量消耗产生显著的临床影响。

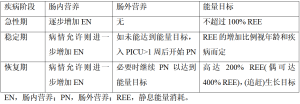

4 利用REE在不同疾病阶段提供最佳能量摄入

4.1 危重疾病急性期和稳定期的能量需求

危重疾病急性期特点在于需要生命器官支持并伴有机体应激反应,因此容易导致过度的分解代谢[68],在此期间能量的产生途径发生变化,且由于失去对常规产能底物的利用控制,替代底物被用于产生能量。传统上,以摄入能量与mREE的百分比值定义过度喂养和喂养不足,其中摄入能量>110% mREE为过度喂养,摄入量<90% mREE则表示喂食不足[69]。然而,在危重疾病急性期,大部分能量需求(高达75%)由内源性产能提供,而与外源性能量提供无关(图2)[71],这种能量的来源方式很容易造成能量供需不平衡,并因此导致临床预后不良。

近期一项回顾性研究[72]发现:相较于接受适度营养供应(90~110% mREE)的患者,过度喂养(>110% mREE)患者的PICU和住院时间显著延长。此外,一项大型多中心随机对照试验[2]表明:与在肠内营养(enteral nutrition,EN)不足时及早(<24 h)开始肠外营养(parenteral nutrition,PN)相比,入院第8天开始PN可提供的能量明显低于预测REE,但却能显著降低院感发生率和提高恢复速度。

新的PICU指南主张在危重病急性期能量摄入不超过REE[10-11]。此外,建议根据喂养方案或指南逐步增加EN直至达标,并将PICU第1周结束时的能量摄入目标定为EN不低于每日能量需求的2/3(表5)[10-11]。以上指南基于一些观察性研究,这些观察性研究表明,接受适度营养摄入的患者具有更好的临床转归[1,3,72]。然而,并非所有研究都测量了REE,目前也没有干预性研究确定改善危重儿童预后的精确能量摄入量。一项系统综述[73]及随后的观察性研究[7]发现:每天57 kcal/kg的最低摄入量(每天1.5 g/kg蛋白质)与正氮平衡相关。

Full table

4.2 危重疾病恢复期的能量需求

疾病恢复期始于患者重新活动和应激反应趋于正常,此阶段可持续数月之久。在此期间,机体代谢进一步由分解代谢向合成代谢转化,蛋白质合成大于分解,继而出现组织修复和(追赶)生长[68]。因此,此期能量需求可能会大幅增加,甚至超过健康儿童的正常能量需求(图2)[70,74]。最新指南[10]指出:度过急性期后,能量的摄入应包括急性期能量负债、机体活动,以及康复和生长需要几个方面(表5)。但仅有少数几项研究评估了恢复阶段的能量需求,其研究目标主要为心脏疾病和烧伤儿童。最近有研究[75]表明:对于主要因心脏疾病入PICU且平均PICU住院时间为50 d的危重婴儿,将能量目标定为2倍预测REE的营养方案,可使该类儿童体重增加与健康儿童相当。在先天性心脏病手术恢复期,2~3倍的REE供给[120~150 kcal/(kg·d)]被认为是婴儿体重增加所必需,对于仍存在血流动力学改变的婴儿[76-77],甚至建议高达4倍REE[200 kcal/(kg·d)]的能量供应。在烧伤患者中,营养需求增加的高代谢状态在伤后2年内仍可出现[59,62,78]。一项1988年的研究[79]表明,该类患者的应摄入大约1.6倍REE以维持体重。

4.3 RQ的应用

RQ可帮助评估底物利用率和/或营养支持,并判断过度喂养和喂养不足。由表1可见,脂肪氧化的RQ为0.7,而蛋白质和碳水化合物氧化的RQ分别为0.8和1.0。碳水化合物摄入量高于机体氧化能力会引起脂肪生成,导致RQ>1.0,因此RQ可作为识别过度喂养的标志[80]。此外,当机体利用储存的内源性脂肪产能来满足能量需求时,RQ可降至0.85以下[59]。然而,RQ的临界值(<0.85、0.85~1.0、>1.0)与当前使用的喂养不足和过度喂养的标准(即摄入量和mREE比率)仅存在中等强度对应关系[81-82]。因此,有研究提议将RQ测量值和预测值[以营养摄入中碳水化合物和脂肪的比例计算(RQmacr)]差异大于0.05作为过度喂养的定义[83],由于RQ在PICU住院期间可随疾病阶段变化而改变,这一定义可能更有助于识别过度喂养。尽管RQ可用于识别喂养不足和过度喂养以及监测营养支持的耐受性,但由于个体独特的代谢“指纹”或“特征”,即患者遗传得来的特定代谢机制的存在,不同个体在不同阶段对应激产生的反应存在特异性和不可预测性,因此无法将RQ用于“微调”性营养治疗。

总体而言,在急性期后,测量REE和RQ可有助于指导营养治疗和增加与REE相关的营养摄入,直至实现(追赶)生长及组织修复。

5 结论

对危重儿童而言,临床医生扮演着制定最佳供能方案、避免喂养不足和过度喂养的角色。

急性期应根据患者的耐受性逐步增加能量摄入,且不超过Schofield方程的预测REE[21]。此后鉴于能量债务、机体活动、康复及生长需要,能量摄入可适当增加至REE的1~2倍。某些患者的REE可能需要经过验证的热量计测量得出。除测量REE外,RQ也是指导营养摄入的有效工具。在评估危重儿童的能量需求时,建议配备包括专门营养师在内的营养团队来指导能量摄入和营养支持。

未来的研究需要为这一特定人群验证一种新的热量计,包括新生儿和婴儿以及高吸入氧浓度的患者。同时,需要开发更准确的REE预测公式或其他测量能量消耗的方法。

声明

基金:无。

脚注

出处和同行评议:本文受客座编辑(LyvonneTume、Frederic Valla 和 Sascha Verbruggen)委托,用于儿科医学杂志“危重疾病儿童营养”系列文章发表。本文已送客座编辑和编辑部组织的外部同行评审。

利益冲突:作者已完成ICMJE统一披露表(来源:https://pm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/pm-20-62/coif)。《危重疾病儿童营养》系列由编辑部委托写作,无任何资金或赞助。CJC感谢Baxter、Nutricia在文章写作之外提供的非财务支持。作者无其他利益冲突声明。

道德声明:作者对本文所有内容负责,以确保任何关于文章准确性或完整性的问题得以恰当探讨和解决。

开放获取声明:这是一篇根据知识共享署名-非商业性使用-禁止衍生4.0国际许可证(CCBY-NC-ND 4.0)发表的开放获取文章,该许可证严格规定文章在不进行任何更改、编辑且被正确引用(包括正式出版物的DOI和许可证链接)的条件下进行非商业性复制和传阅。见:https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/。

References

- Mehta NM, Bechard LJ, Cahill N, et al. Nutritional practices and their relationship to clinical outcomes in critically ill children--an international multicenter cohort study. Crit Care Med 2012;40:2204-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fivez T, Kerklaan D, Mesotten D, et al. Early versus Late parenteral nutrition in critically ill children. New Engl J Med 2016;374:1111-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wong JJ, Han WM, Sultana R, et al. Nutrition Delivery Affects Outcomes in Pediatric Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2017;41:1007-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- European Food Safety Authority. Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for energy. EFSA J 2013;11:3005. [Crossref]

- FAO/WHO/UNU. Human energy requirements :report of a Joint FAO/WHO/UNU Expert Consultation: Rome, 17-24 October 2001.

- Butte NF, Wong WW, Hopkinson JM, et al. Energy requirements derived from total energy expenditure and energy deposition during the first 2 y of life. Am J Clin Nutr 2000;72:1558-69. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jotterand Chaparro C, Laure Depeyre J, Longchamp D, et al. How much protein and energy are needed to equilibrate nitrogen and energy balances in ventilated critically ill children? Clin Nutr 2016;35:460-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Takala J, Meriläinen P. Handbook of gas exchange and indirect calorimetry. Helsinki: Datex, 1991.

- Weir JB. New methods for calculating metabolic rate with special reference to protein metabolism. J Physiol 1949;109:1-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tume LN, Valla FV, Joosten K, et al. Nutritional support for children during critical illness: European Society of Pediatric and Neonatal Intensive Care (ESPNIC) metabolism, endocrine and nutrition section position statement and clinical recommendations. Intensive Care Med 2020;46:411-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mehta NM, Skillman HE, Irving SY, et al. Guidelines for the Provision and Assessment of Nutrition Support Therapy in the Pediatric Critically Ill Patient: Society of Critical Care Medicine and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2017;18:675-715. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mehta NM, Compher C A.S.P.E.N.. Clinical Guidelines: nutrition support of the critically ill child. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2009;33:260-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kyle UG, Arriaza A, Esposito M, et al. Is indirect calorimetry a necessity or a luxury in the pediatric intensive care unit? JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2012;36:177-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van der Kuip M, Oosterveld MJ. Nutritional support in 111 pediatric intensive care units: a European survey. Intensive Care Med 2004;30:1807-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kerklaan D, Fivez T, Mehta NM, et al. Worldwide Survey of Nutritional Practices in PICUs. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2016;17:10-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Valla FV, Gaillard-Le Roux B, Ford-Chessel C, et al. A nursing survey on nutritional care practices in French-speaking pediatric intensive care units: NutriRéa-ped 2014. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2016;62:174-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Takala J, Keinanen O, Vaisanen P, et al. Measurement of gas exchange in intensive care: laboratory and clinical validation of a new device. Crit Care Med 1989;17:1041-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tissot S, Delafosse B, Bertrand O, et al. Clinical validation of the Deltatrac monitoring system in mechanically ventilated patients. Intensive Care Med 1995;21:149-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weyland W, Weyland A, Fritz U, et al. A new paediatric metabolic monitor. Intensive Care Med 1994;20:51-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mihatsch WA, Braegger C, Bronsky J, et al. ESPGHAN/ESPEN/ESPR/CSPEN guidelines on pediatric parenteral nutrition. Clin Nutr 2018;37:2303-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schofield WN. Predicting basal metabolic rate, new standards and review of previous work. Hum Nutr Clin Nutr 1985;39:5-41. [PubMed]

- Harris JA, Benedict GF. A biometric study of basal metabolism in man. Washington: Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1919.

- Jotterand Chaparro C, Moullet C, Taffe P, et al. Estimation of Resting Energy Expenditure Using Predictive Equations in Critically Ill Children: Results of a Systematic Review. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2018;42:976-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Talbot FB. Basal metabolism standards for children. AM J Child 1938;55:455.

- Jotterand Chaparro C, Taffe P, Moullet C, et al. Performance of Predictive Equations Specifically Developed to Estimate Resting Energy Expenditure in Ventilated Critically Ill Children. J Pediatr 2017;184:220-6.e5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- White MS, Shepherd RW, McEniery JA. Energy expenditure in 100 ventilated, critically ill children: Improving the accuracy of predictive equations. Crit Care Med 2000;28:2307-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Meyer R, Kulinskaya E, Briassoulis G, et al. The Challenge of Developing a New Predictive Formula to Estimate Energy Requirements in Ventilated Critically Ill Children. Nutr Clin Pract 2012;27:669-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mehta NM, Smallwood CD, Joosten KF, et al. Accuracy of a simplified equation for energy expenditure based on bedside volumetric carbon dioxide elimination measurement--a two-center study. Clin Nutr 2015;34:151-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Taylor RM, Cheeseman P, Preedy V, et al. Can energy expenditure be predicted in critically ill children? Pediatr Crit Care Med 2003;4:176-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mouzaki M, Schwartz SM, Mtaweh H, et al. Can Vco2-Based Estimates of Resting Energy Expenditure Replace the Need for Indirect Calorimetry in Critically Ill Children? JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2017;41:619-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kerklaan D, Augustus ME, Hulst JM, et al. Validation of ventilator-derived VCO2 measurements to determine energy expenditure in ventilated critically ill children. Clin Nutr 2017;36:452-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van der Kuip M, de Meer K, Westerterp KR, et al. Physical activity as a determinant of total energy expenditure in critically ill children. Clin Nutr 2007;26:744-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Joosten KF, Verhoeven JJ, Hop WC, et al. Indirect calorimetry in mechanically ventilated infants and children: accuracy of total daily energy expenditure with 2 hour measurements. Clin Nutr 1999;18:149-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Matthews DS, Bullock RE, Matthews JN, et al. Temperature response to severe head injury and the effect on body energy expenditure and cerebral oxygen consumption. Arch Dis Child 1995;72:507-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Coss-Bu JA, Jefferson LS, Walding D, et al. Resting energy expenditure in children in a pediatric intensive care unit: comparison of Harris-Benedict and Talbot predictions with indirect calorimetry values. Am J Clin Nutr 1998;67:74-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ismail J, Bansal A, Jayashree M, et al. Energy Balance in Critically Ill Children With Severe Sepsis Using Indirect Calorimetry: A Prospective Cohort Study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2019;68:868-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Briassoulis G, Venkataraman S, Thompson AE. Energy expenditure in critically ill children. Crit Care Med 2000;28:1166-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gebara BM, Gelmini M, Sarnaik A. Oxygen consumption, energy expenditure, and substrate utilization after cardiac surgery in children. Crit Care Med 1992;20:1550-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vernon DD, Witte MK. Effect of neuromuscular blockade on oxygen consumption and energy expenditure in sedated, mechanically ventilated children. Crit Care Med 2000;28:1569-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lemson J, Driessen JJ, van der Hoeven JG. The effect of neuromuscular blockade on oxygen consumption in sedated and mechanically ventilated pediatric patients after cardiac surgery. Intensive Care Med 2008;34:2268-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cai W, Tao Y, Tang Q, et al. Study on energy metabolism in perioperative infants. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2006;16:227-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shanbhogue RL, Jackson M, Lloyd DA. Operation does not increase resting energy expenditure in the neonate. J Pediatr Surg 1991;26:578-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shanbhogue RL, Lloyd DA. Absence of hypermetabolism after operation in the newborn infant. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 1992;16:333-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Groner JI, Brown MF, Stallings VA, et al. Resting energy expenditure in children following major operative procedures. J Pediatr Surg 1989;24:825-7; discussion 827-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Powis MR, Smith K, Rennie M, et al. Effect of major abdominal operations on energy and protein metabolism in infants and children. J Pediatr Surg 1998;33:49-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Botrán M, Lopez-Herce J, Mencia S, et al. Relationship between energy expenditure, nutritional status and clinical severity before starting enteral nutrition in critically ill children. Br J Nutr 2011;105:731-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jones MO, Pierro A, Hammond P, et al. The metabolic response to operative stress in infants. J Pediatr Surg 1993;28:1258-62; discussion 1262-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jones MO, Pierro A, Hashim IA, et al. Postoperative changes in resting energy expenditure and interleukin 6 level in infants. Br J Surg 1994;81:536-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jones MO, Pierro A, Hammond P, et al. The effect of major operations on heart rate, respiratory rate, physical activity, temperature and respiratory gas exchange in infants. Eur J Pediatr Surg 1995;5:9-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oosterveld MJS, Van Der Kuip M, De Meer K, et al. Energy expenditure and balance following pediatric intensive care unit admission: A longitudinal study of critically ill children. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2006;7:147-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Turi RA, Petros AJ, Eaton S, et al. Energy metabolism of infants and children with systemic inflammatory response syndrome and sepsis. Ann Surg 2001;233:581-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Feferbaum R, Leone C, Siqueira AA, et al. Rest energy expenditure is decreased during the acute as compared to the recovery phase of sepsis in newborns. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2010;7:63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bauer J, Hentschel R, Linderkamp O. Effect of sepsis syndrome on neonatal oxygen consumption and energy expenditure. Pediatrics 2002;110:e69 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Phillips R, Ott L, Young B, et al. Nutritional support and measured energy expenditure of the child and adolescent with head injury. J Neurosurg 1987;67:846-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moore R, Najarian MP, Konvolinka CW. Measured energy expenditure in severe head trauma. J Trauma 1989;29:1633-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mtaweh H, Smith R, Kochanek PM, et al. Energy expenditure in children after severe traumatic brain injury. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2014;15:242-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Havalad S, Quaid MA, Sapiega V. Energy expenditure in children with severe head injury: lack of agreement between measured and estimated energy expenditure. Nutr Clin Pract 2006;21:175-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tilden SJ, Watkins S, Tong TK, et al. Measured energy expenditure in pediatric intensive care patients. Am J Dis Child 1989;143:490-2. [PubMed]

- Mlcak RP, Jeschke MG, Barrow RE, et al. The influence of age and gender on resting energy expenditure in severely burned children. Ann Surg 2006;244:121-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Suman OE, Mlcak RP, Chinkes DL, et al. Resting energy expenditure in severely burned children: analysis of agreement between indirect calorimetry and prediction equations using the Bland-Altman method. Burns 2006;32:335-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jeschke MG, Chinkes DL, Finnerty CC, et al. Pathophysiologic response to severe burn injury. Ann Surg 2008;248:387-401. [PubMed]

- Jeschke MG, Gauglitz GG, Kulp GA, et al. Long-term persistance of the pathophysiologic response to severe burn injury. PLoS One 2011;6:e21245 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hart DW, Wolf SE, Mlcak R, et al. Persistence of muscle catabolism after severe burn. Surgery 2000;128:312-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- de Klerk G, Hop WC, de Hoog M, et al. Serial measurements of energy expenditure in critically ill children: useful in optimizing nutritional therapy? Intensive Care Med 2002;28:1781-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mtaweh H, Soto Aguero MJ, Campbell M, et al. Systematic review of factors associated with energy expenditure in the critically ill. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2019;33:111-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jeschke MG, Barrow RE, Herndon DN. Extended hypermetabolic response of the liver in severely burned pediatric patients. Arch Surg 2004;139:641-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Finnerty CC, Herndon DN, Przkora R, et al. Cytokine expression profile over time in severely burned pediatric patients. Shock 2006;26:13-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Joosten KF, Kerklaan D, Verbruggen SC. Nutritional support and the role of the stress response in critically ill children. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2016;19:226-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McClave SA, Lowen CC, Kleber MJ, et al. Are patients fed appropriately according to their caloric requirements? JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 1998;22:375-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Joosten KFM, Eveleens RD, Verbruggen SCAT. Nutritional support in the recovery phase of critically ill children. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2019;22:152-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Preiser JC, van Zanten ARH, Berger MM, et al. Metabolic and nutritional support of critically ill patients: consensus and controversies. Crit Care 2015;19:35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Larsen BMK, Beggs MR, Leong AY, et al. Can energy intake alter clinical and hospital outcomes in PICU? Clin Nutr ESPEN 2018;24:41-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bechard LJ, Parrott JS, Mehta NM. Systematic review of the influence of energy and protein intake on protein balance in critically ill children. J Pediatr 2012;161:333-9.e1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Joosten K, Embleton N, Yan W, et al. ESPGHAN/ESPEN/ESPR/CSPEN guidelines on pediatric parenteral nutrition: Energy. Clin Nutr 2018;37:2309-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eveleens RD, Dungen DK, Verbruggen SC, et al. Weight improvement with the use of protein and energy enriched nutritional formula in infants with a prolonged PICU stay. J Hum Nutr Diet 2019;32:3-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Medoff-Cooper B, Irving SY. Innovative strategies for feeding and nutrition in infants with congenitally malformed hearts. Cardiol Young 2009;19:90-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nicholson GT, Clabby ML, Kanter KR, et al. Caloric intake during the perioperative period and growth failure in infants with congenital heart disease. Pediatr Cardiol 2013;34:316-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hart DW, Wolf SE, Herndon DN, et al. Energy expenditure and caloric balance after burn: increased feeding leads to fat rather than lean mass accretion. Ann Surg 2002;235:152-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hildreth MA, Herndon DN, Desai MH, et al. Reassessing caloric requirements in pediatric burn patients. J Burn Care Rehabil 1988;9:616-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McClave SA, Snider HL. Use of indirect calorimetry in clinical nutrition. Nutr Clin Pract 1992;7:207-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hulst JM, van Goudoever JB, Zimmermann LJ, et al. Adequate feeding and the usefulness of the respiratory quotient in critically ill children. Nutrition 2005;21:192-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dokken M, Rustøen T, Stubhaug A. Indirect calorimetry reveals that better monitoring of nutrition therapy in pediatric intensive care is needed. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2015;39:344-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kerklaan D, Hulst JM, Verhoeven JJ, et al. Use of Indirect Calorimetry to Detect Overfeeding in Critically Ill Children: Finding the Appropriate Definition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2016;63:445-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

王彩虹。河北中石油中心医院。2002.09-2007.07就读于河北医科大学临床医学专业,2007.09-2010.07就读于北京大学医学部儿科学专业,研究方向免疫学,研究单位,首都儿科研究所。毕业后从事儿科临床工作至今。(更新时间:2021/7/14)

(本译文仅供学术交流,实际内容请以英文原文为准。)

Cite this article as: Veldscholte K, Joosten K, Jotterand Chaparro C. Energy expenditure in critically ill children . Pediatr Med 2020;3:18.